Assistant Professor, Anthropology

The University of British Columbia, Okanagan

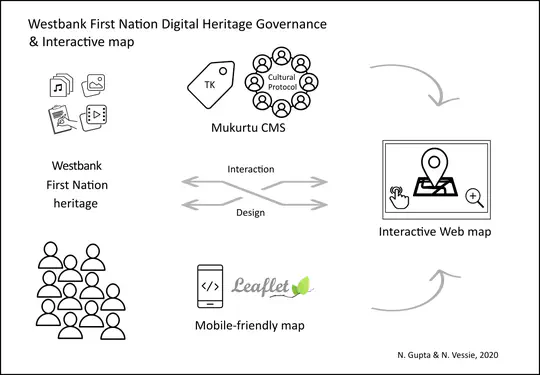

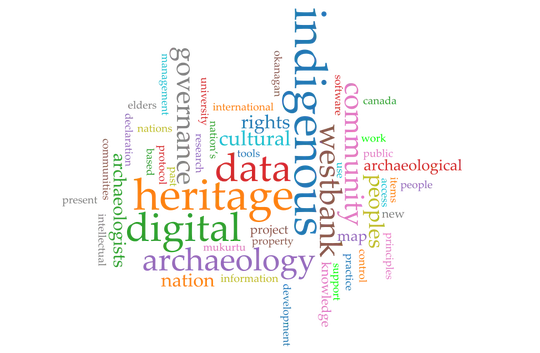

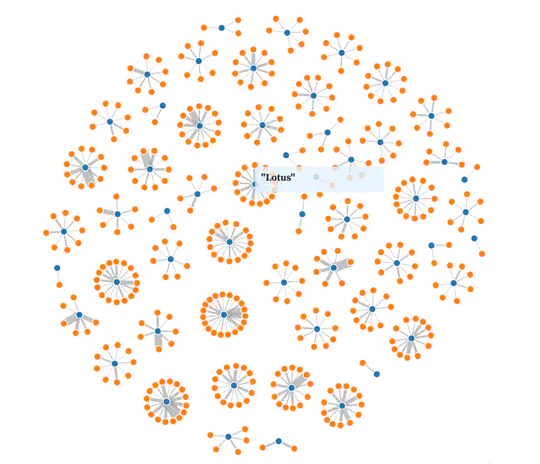

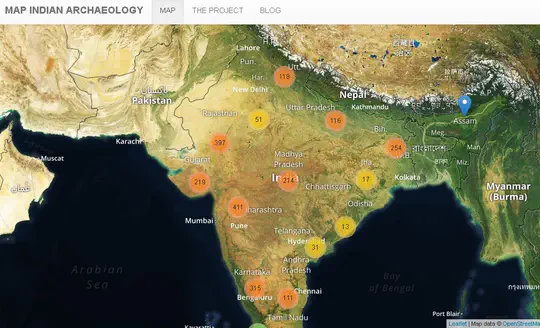

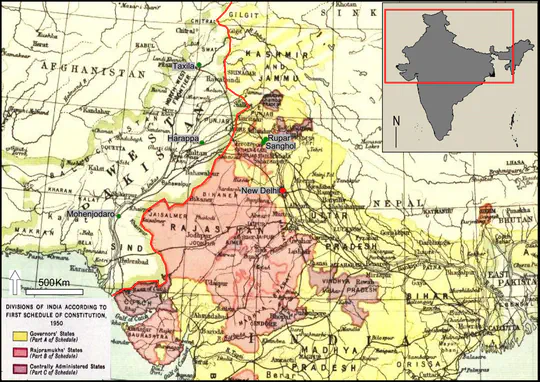

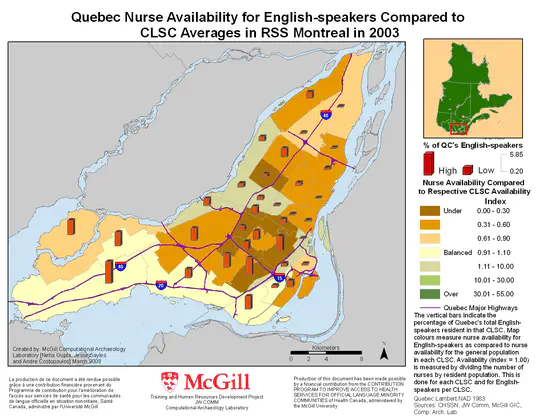

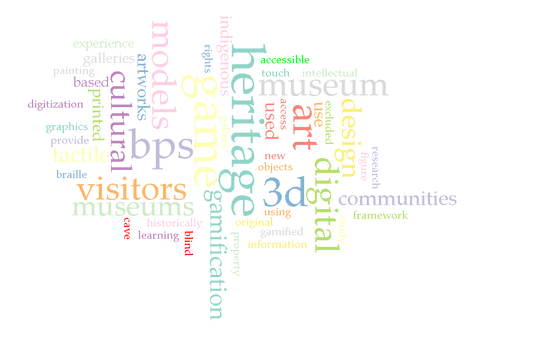

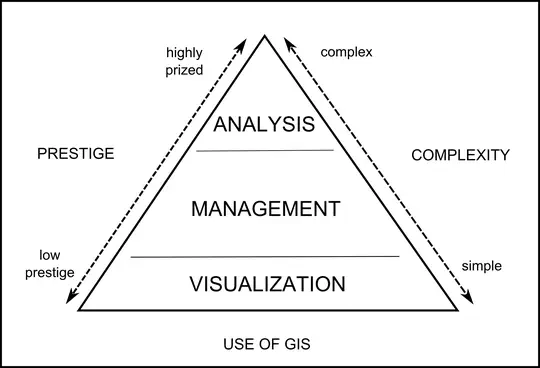

I am Assistant Professor in Anthropology at The University of British Columbia. My research programme examines and addresses geospatial and digital methods in anti-colonial and Indigenous studies of heritage (including archaeology). My research interests are geovisualization and GIS, place-based heritage, data practice, community governance of data, anti-racism and archaeology in India and Canada. I build and expand on these interests through DARE | Digital Archaeology Research Environment, a Canada Foundation for Innovation laboratory at UBC Okanagan.

- Digital and Geospatial Methods

- Postcolonial, decolonial, anti-colonial and Indigenous studies of heritage

- Archaeology in India and Canada

PhD Anthropology, 2012

McGill University

MSc GIS and Spatial Analysis in Archaeology, 2002

University College London

BSc (Hons.) Archaeological Sciences, 2001

University of Toronto

Featured Publications

Recent Publications

Teaching

Course syllabi available

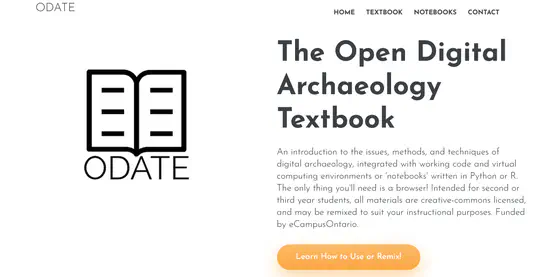

- Digital Arts and Humanities Seminar (Graduate level)

- Introduction to World Archaeology (100-level)

- Archaeological Inquiry & Practice (200-level)

- Digital Methods in Archaeology & Heritage (300-level)

- Settling Down: An Archaeology of Early State Societies (300-level)

- Digital Anthropology (400-level)

- Introduction to Geographic Information Systems (200-level)

- Scientific Applications in Archaeology (400-level)

Projects

Recent Talks & Workshops

Contact

Email me: neha(dot)gupta(at)ubc(dot)ca